Articulo disponible en español en este enlace.

Farmville Detention Center stands surrounded by dense forests and barren grassy pastures, a three-hour drive from Washington D.C. into the Central Virginia plains. The facility is one of two detention centers in the Commonwealth, and one of the major holding places for migrants detained in D.C., Maryland, and Virginia. Since it opened in 2010, Farmville has accrued over a decade of mistreatment allegations, with new complaints emerging this year.

On October 19, 2025, detainees held in Farmville Detention Center accused the facility of serving them contaminated, rotten food. Virginia lawyers and activists said detainees described ingesting small white worms in their meals and later refusing meals in response. In a press release from the National Lawyers' Guild, they called for safe, nutritious meals and basic health standards.

CoreCivic, the new owners and administrators of the detention center, “unequivocally” denied the incidents when contacted by El Tiempo Latino, as did representatives from ICE. Still, social justice organizations like LaColectiVA and other members of the Free Them All VA Coalition have spent years tracking and amplifying concerns of how detainees are treated at Farmville. Amid an unprecedented scale-up of ICE detention operations, the new allegations of unsanitary conditions have them sounding alarms about the facility yet again.

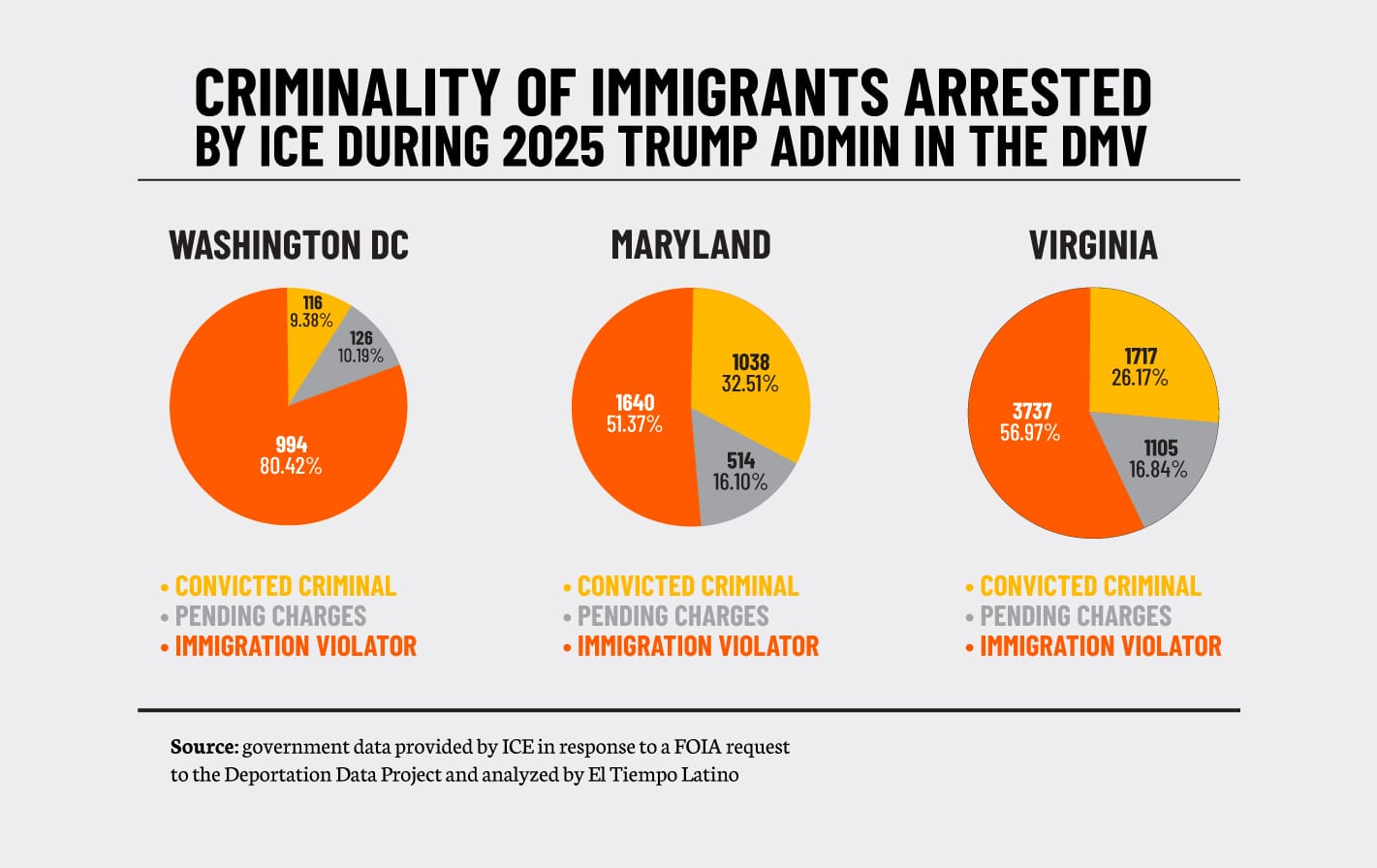

As of December 2025, ICE statistics report that 75% of Farmville’s detainees had never been convicted of a crime. Now, their family members, legal teams, and community organizers maintain that longtime residents of the DMV are being subjected to “abhorrent” conditions that they say surpass even ICE’s own detention standards.

Allison Beltran, a community organizer working with immigrant families across the DMV, believes that the isolated, countryside location of Farmville Detention Center is no accident. Working with LaColectiVA, a Virginian social justice and equity collective, Beltran often receives pleas from community members who “simply don’t have access” to visit their family members detained at Farmville. They come to LaColectiVA for help, unable to take the time off work or endure the full day's journey to reach their detained family members.

“It’s a remote location, a rural location, that isn’t accessible for people”, said Beltran. “But that’s on purpose”.

In 2008, Immigration Centers of America (ICA) was contracted by ICE and the local government of Farmville, Virginia to open a detention center on the outskirts of the small Virginia town. When the center opened in 2010, it was the largest immigration detention facility in the mid-Atlantic region.

Over a decade since its opening, Farmville Detention Center has accumulated a troubling record of credible mistreatment allegations. El Tiempo Latino reviewed documented incidents ranging from food contamination and threats of violent retaliation to a covid outbreak that infected over 90% of detainees and temporarily shut the facility down.

Though legal settlements following the COVID outbreak strictly limited the center's operations in 2022, it has since resumed detaining migrants, only further strengthened by the nationwide expansion of immigration enforcement beginning this year.

In June of 2025, Farmville was purchased by CoreCivic, a for-profit private corrections company operating prisons, jails, and detention centers across the US, 80 facilities in over 20 states. Their newest ICE contracts expect them to “rake in” a $300 million payout, given the unprecedented increase in deportation operations by the Trump administration.

Over the past 15 years, thousands of migrants have been detained within the walls of Farmville Detention Center, holding a maximum of 732 people at a time as they await immigration proceedings or deportation. Under ICE’s own management standards, detention is formally classified as “non-punitive”. Immigration detention is a civil process under federal law, not a criminal sentence, and being undocumented is not itself a criminal offense in Virginia, Maryland, or Washington, D.C.

Audrey Vorhees is a Senior Associate Immigration Attorney based in the DMV. At Vorhees’ law firm, she says that “all of the clients we have detained at Farmville are people who were picked up in Virginia, DC, or Maryland”. She described her caseload and the wide range of circumstances it covers, from 19 year olds picked up at DC traffic stops, to working fathers worried about leaving their families behind.

“Your local community members, your neighbors, your gardeners, your day laborers, those are the people that, if they end up being affected by these ICE enforcement actions, they likely are going to end up in Farmville or in Caroline”, said Vorhees.

With LaColectiVA, Beltran is also working firsthand to assist immigrants and their families through the difficulties of detention. She spoke specifically of a family of migrant construction workers from Guatemala, a 21 year old who was detained with his brother after running a red light in his truck. Their father had just chosen to self-deport back to Guatemala; only days later, his son was detained.

“We’re often supporting young people like him. People who are simply working, being a part of their communities, on their way to work, living lives like normal”, said Beltran. “They’re experiencing a moment where the police are profiling, criminalizing, and unfortunately taking them in this pipeline of detention”.

From day laborers awaiting assignments on Virginia street corners, to Uber drivers motoring

through the streets of DC, interviewees described the kinds of men they’d seen detained in Farmville as hard workers with DMV families. ICE’s own statistics confirm that three-quarters of the men currently held at Farmville, are categorized as “non-criminal” detainees. 71% have no ICE threat level, meaning that ICE has assigned them no designation of criminal or safety risk.

Funneling through other local centers like Caroline Detention Facility or Moshannon Valley Processing Center in Pennsylvania, Vorhees’ clients are, in her experience, local residents caught up in unprecedented civil immigration enforcement. But at Farmville, interviewees say that these men are under conditions that cross from “non-punitive” to inhumane.

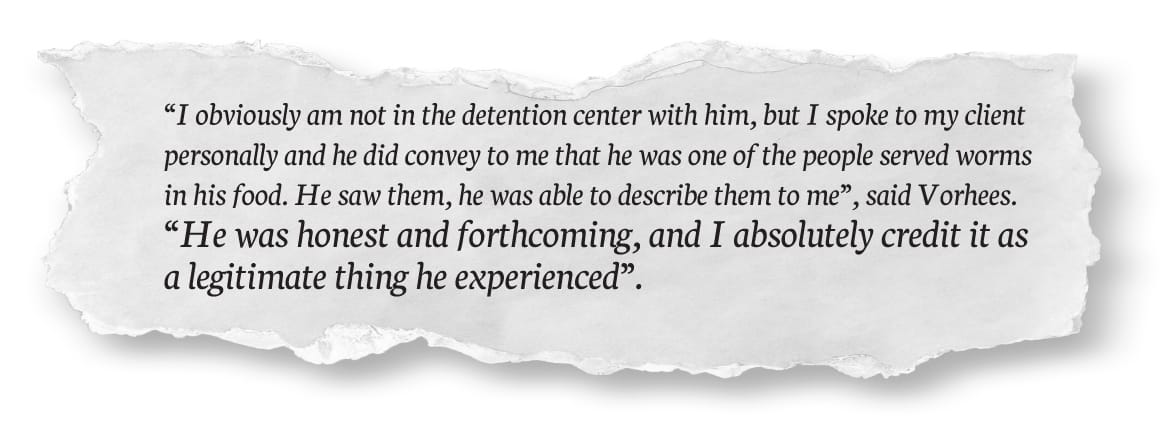

Detainees held in Farmville Detention Center this past October say that they were served a contaminated, rotten meal in October. These men, including one of Vorhees’ own clients, reported seeing and ingesting small white worms in their dinner, and refused to eat the next three meals they were served the next day in protest.

The incident was first reported in a press release from the National Immigration Project of the National Lawyers’ Guild, where detainees describe “feeling sick” at the sight of small worms in their food, and pleading for “nutritious food and basic health and safety measures” in response.

According to the release, food served to Farmville detainees is prepared once every four days, mixed with fresh food and leftovers and required to go no more than 2 hours without refrigeration.

El Tiempo Latino reached out to CoreCivic for comment on the October 19 allegations of worms in the food served to Farmville detainees. Their Manager of Public Affairs, Brian Todd, said that “there’s no validity to the claims of rotten food and worms at FDC. Upon receiving concerns one evening, facility leadership immediately examined the food and found no evidence of contamination or foreign materials”.

An ICE Spokesperson also told El Tiempo Latino that “The claims about the condition of the food at the Farmville Detention Center are unequivocally false”. According to ICE, “the claims of spoilage stemmed from a single detainee who hoarded food that he purchased from the commissary in his dormitory to the point of spoilage. This was not an issue with the food served by the facility”.

While ICE statements specified that the contaminated food had only involved one man, the NIP press release alleges that 98 men, an entire unit of the facility, returned the food they were served after fellow inmates presented evidence of worms in their food. On a confidential video call two days later, Vorhees heard her client describe how he and others in his sector were now purchasing ramen from the commissary to refuse the food they were being served.

The NIP press release alleges that staff responded to the hunger strike by threatening detainees and their access to food sold at the commissary. According to Vorhees, however, even the purchased food was not necessarily safe, causing her client “intense stomach aches”. Vorhees’ client told her that said pain has since caused his unit to call off the strike, though he says he now carefully inspects every meal he is served.

“I obviously am not in the detention center with him, but I spoke to my client personally and he did convey to me that he was one of the people served worms in his food. He saw them, he was able to describe them to me”, said Vorhees. “He was honest and forthcoming, and I absolutely credit it as a legitimate thing he experienced”.

Concerns about contamination, mistreatment, and negligence at Farmville are not new. Detainees in 2015 were also served worms in their food, with ICE documents confirming they saw “bug larva” in two different meals, served in March and February of that year. A letter from the U.S. ICE Office of Acquisition Management details how staff suspected detainees of tampering and threatened those who spoke out with criminal charges or immigration penalties. The threats were later found to violate ICE disciplinary standards.

Those same ICE records indicate that retaliation at Farmville extended beyond threats, with documented cases of staff using force against detainees. One man was repeatedly pepper-sprayed while restrained in handcuffs and leg-irons and held in a padded cell. Another was held for four days in restraint chairs/beds despite medical records showing he was uninjured and cooperative. Both incidents were found to violate detention standards, with uses of force that were “not sufficiently justified.”

In perhaps the most high-profile case of mistreatment allegations at Farmville, a 2020 lawsuit claimed that ICE sparked a massive outbreak by knowingly transferring COVID-positive detainees into the center. At the time, it was the largest COVID outbreak among any detention facility in the country: a peak of 93% inmates tested positive.

The lawsuit ended with a 2022 legal settlement imposing strict operational limits on Farmville, restricting a maximum 25% holding capacity until the COVID public health emergency ended.

Once ICE resumed an increased use of Farmville Detention Center in 2023, use of the facility steadily increased, then skyrocketed in 2025.

With so many years of service organizing through LaColectiVA, supporting migrants through the physical and psychological toll of detention, Beltran believes the worst may still be unreported. To her, the mistreatment allegations that she’s helped to track and document show only a fraction of the reality inside of facilities like Farmville.

“People are left wondering what’s really going on, and you don’t find out until you hear from people who [make it] outside”, said Allison. “When they’re finally free to unload all of these stories on you, you realize it’s a lot worse than anyone really thinks it is”.

The allegations emerging from Farmville are not unique. According to Vorhees, neither is

Farmville itself. “Farmville is just one detention center of dozens and dozens across the country”, she said. “And I think what’s really disheartening is that these things are happening all over the country”.

As of December 2025, ICE has detained a total of 68,442 people in the current fiscal year. Of those, only 26%, or 17,879 people, had prior criminal convictions. They average a 49 day length of stay in detention centers nationwide. More than 500 credible reports of mistreatment allegations have been documented across these detention centers in at least 13 states, according to an investigation from the office of Senator Jon Ossoff.

Through her work, Vorhees said she’s heard similar stories emerging from the other detention centers local to the east coast, Moshannon Valley Processing Center in Pennsylvania, and Caroline Detention Facility in Virginia. But even though Farmville and Caroline are here in Virginia, she emphasized that these allegations “really [are] a nationwide issue”.

From her perspective, Vorhees hopes that people walk away from stories like hers and her clients’ by “not only calling out the inhumane practices in these detention centers, but also really emphasizing that many of the people in these centers have never been charged with a crime”.

“These are moms and dads who’ve been in the United States for 2 years, who’ve been paying taxes and have no criminal histories”, she said. “These are not criminals”.

For Beltran, the emphasis on criminality is less of a priority for her. Instead, she pushes the urgency of fighting against a cruelty in these centers that she sees as universal.

“I think whether you’ve been here for six months or whether you’ve lived here for 30 years, you have a family or you're paying taxes… none of that matters”, she said. “At the end of the day once you’re inside this system you are just a number and a body and they don’t see your story”.

“They don’t care and they will violate people. They will commit human rights violations”, Beltran claimed.

Beltran’s ties to Farmville extend beyond the stories she hears through her work. She first learned about the facility in 2017, after the father of her children was detained there.

For weeks, she worked through his legal case, attempting to establish the basis for an asylum claim. She spoke to him on the phone, smiling through the stories of what he could tell her about his experience within Farmville. And she returned to their quiet apartment, having to now work to support the rent, food, and livelihood burden that she’d once been able to share.

“You’re now suddenly playing this role of a counselor, psychologist, social worker, a friend, doing so much emotional support for a person that you just might not be prepared to do”, said Beltran. “I’d end up asking, ‘and now who’s going to support me?’”.

In LaColectiVA, she says, Beltran found support within a community of others who’d been impacted by the system. Now, she works to support others, offering her the resources she wishes she once had.

LaColectiVA, in collaboration with other organizations in the Free Them All VA collective, offers support for families navigating detention and deportation, from emergency hotlines to documented fact sheets, available for anyone across DC, Maryland, or Virginia. Beltran says the organization will keep sharing, exposing what’s happening, and organizing from outside to help those within DMV detention centers.

“It doesn’t matter if you’re in Farmville, Riverside, or any other detention center. We’ll continue to support anyone who is detained. We are here to help”, said Beltran.